Bayesian Reasoning in Humans

- Kyle Park

- Nov 4, 2023

- 3 min read

I came across the conditional probability formula multiple times during my math classes in high school, but only recently did I learn about its application in the field of psychology and general human decision-making processes.

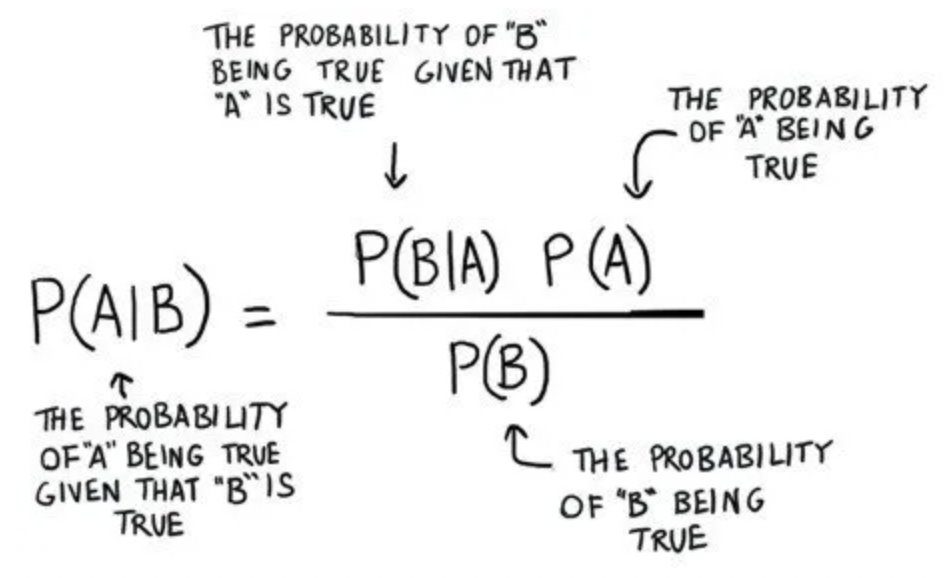

At the most fundamental level, the conditional probability is as follows:

Surprisingly, this formula lies at the heart of how humans learn, reason, and act. In simple terms, Bayesian thinking is the process of calculating initial odds, updating probabilities as new evidence arises, and making the best possible predictions by adjusting the initial prediction. Unlike mechanisms introduced in heuristics, Bayesian thinking procedures are categorized as optimal reasoning.

There are countless examples in our own lives that can be used as an analogy for Bayesian thinking. For instance, we often run into scenarios that deal with medical diagnoses.

Prior: I notice a health issue and decide to visit a local doctor. I know that I do not have any significant issues in my medical history, so I have a prior belief that my concerns will be minor. Thus, I initially believe that there is a low chance of me having a serious medical issue.

Likelihood/Current Data: I talk to the doctor and he conducts several tests. In this hypothetical scenario, the results show a few markers that may indicate a serious medical issue. The test results is considered the current data/likelihood.

Posterior: Applying Bayesian thinking, the doctor puts together the prior belief and relevant test results. The doctor evaluates the situation and concludes that while the prior belief indicates a low chance of having a serious medical condition, the follow-up test results dramatically changes said chance. The doctor appropriately edits the diagnosis and revises the treatment plan to best suit my needs.

To better understand Bayesian thinking, I highly recommend that you watch this introductory video by Julia Galef:

While humans are certainly able to make such rational decisions based on available data, humans are not all perfect Bayesian reasoners due to various forms of heuristics. Just recently, when I purchased a new phone, I experienced psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman's idea of anchoring heuristics.

Behavior: I entered a local electronic store to buy a new phone. I came across a phone with advanced features that had an initial price tag that was higher than most other phones in the store.

Relevant Heuristic Bias/Principle: As discussed in the paper “Judgement under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases” by Tversky and Kahneman, the anchoring heuristic suggests the people often rely on the initial piece of information they get during decision-making processes, regardless of how relevant that piece of information is.

Outcome of Behavior: I knew that the phone I came across was not in my ideal price range and had features that were not necessarily needed for my purposes. Thus, the high price that I initially saw for the phone served as an "anchor" in this case. I ultimately looked at mid-level phones which were less-advanced but still more pricey than similar model in other local tech stores. Thus, my decision was impacted by the "anchor" and eventually led me to spend more on a phone.

As we continue to ponder the optimality of human decision-making, we must also consider several nuances to this idea of heuristic biases. For instance, to what extent does heuristic biases not result in a change in the behavior outcomes? Heuristic biases often change decision-making processes but does that necessarily lead to a change in actual behavior? Alongside heuristic biases, what other external factors play a role in influencing our behaviors in diverse contexts?

Just some food for thought. Enjoy the rest of your day -- and stay curious.

Comments